My cousin Jerry was always fascinated by my grandfather, Jack Howard, who had lived a long life and had many stories to tell. Jerry used to comment with wonder about “all the things he must have seen in his lifetime” and one day, visiting us at our home in south central Connecticut, he had the chance to ask about them.

The question was something to the effect of “What are the most significant new things you’ve seen during your life?”

Jack had been born in May 1875, so he had certainly seen a lot. For example, Alexander Graham Bell’s first patent for telephones was issued within a year of his birth, in 1876. Jack’s father, James Henry Howard, was an inventor in the same nineteenth-century sense as Edison and Bell, and was also issued several patents for improvements in telephone technology. Indeed in the 1880s he became the Vice President of the Tropical American Telephone Company, which held exclusive rights for the sale of telephone equipment from the Bell system in most countries of Central and South America.1 The rights to all his father’s patents were passed to Jack in 1912, so he must have had very keen awareness of how transformative telephone service had been in his lifetime.

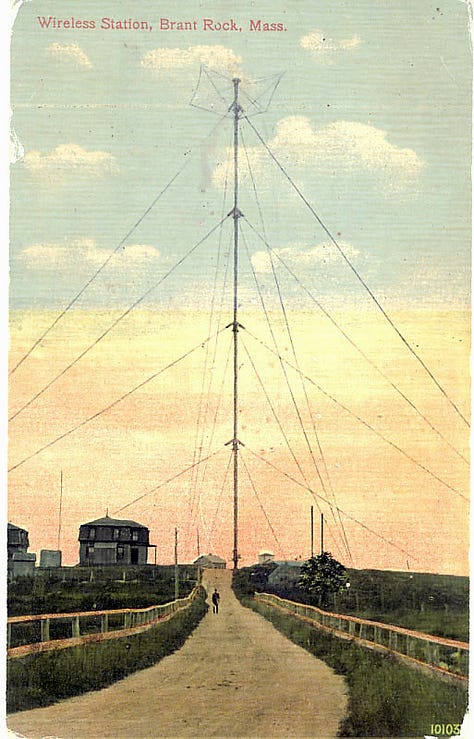

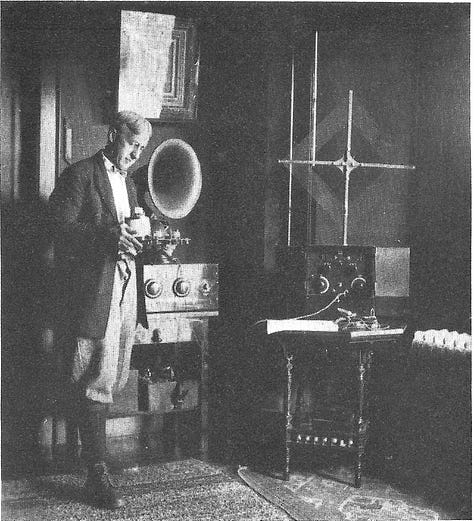

Electricity was introduced for civic and domestic use during Jack’s lifetime, too. In his early adolescent years street lamps transitioned from gas to electricity, and electric current began to be deployed into people’s homes. Jack was to spend his career working with electrically powered vehicles and materials handling equipment, and toward the end of his life he began a lengthy essay on the history and inevitable return of electric cars. Of course there was also radio. Reginald Fessenden’s alleged first broadcast of entertainment via AM radio took place in 1906 at Brant Rock, Massachusetts; Jack would surely have been aware of the 128-meter antenna tower there,2 scarcely ten miles from Trouants Island where he and his family passed their summers.3 (Jack also gave public talks about radio technology in those days.)

In addition, he had seen the transformation of both transportation and American society by automobiles; silent, then talking pictures; phonographs; transistors and microchips; and all the lethal technology associated with merciless warfare.

So how did Jack respond to Jerry’s question?

We all thought it was funny at the time. His immediate response was, “the vacuum cleaner.” Astonishment gave way to thoughts of how much he must have hated carrying the rugs out to the line to beat them clean with a wire or wicker carpet beater, then returning inside to sweep and mop the floors. With all he had witnessed, this was the first thing that came to mind? Reflection, though, makes the remark more sympathetic. “Spring cleaning” used to refer to the annual strenuous cleaning effort when winter subsided and months of household filth could once again be purged to the outside. The power-hungry cleaning technology we know as the vacuum cleaner or “hoover” did not become mainstream until the 1920s and later, when new value was placed on the benefits of “hygienic” and “sanitary” domestic conditions. So Jack had had some fifty years of beating dusty rugs to bring him to this perspective.

The second response made us smile, too. “The refrigerator,” he declared.

At that time we younger people all took it for granted. Almost. I did know the story of the first electric refrigerator in the Howard household: my father had witnessed it and told the story often. It must have been in the late 1920s or early 1930s. It was to be a surprise for my grandmother, Helen, who was always busy in the house, and according to the story it took some effort to get her away long enough to bring the refrigerator in without being observed. When she came back and Jack and the kids proudly presented it to her, all she said was “Why did you put it there?” The story was never about the refrigerator, but about Helen, who could cast a cool eye on anything except her children and her grandchildren.

So I had at least some understanding of how incredibly important refrigerators were. Growing up we had what must have been a second-hand refrigerator with a small freezer compartment. It was noisy and the kitchen floor vibrated when the compressor kicked into action. It was also compact and sturdy, coated thick with pure white porcelain. This was eventually replaced by a new model with many plastic parts and a skin of thin metal, purchased at a discount with the help of my uncle who managed the parts department at Frigidaire’s headquarters in Kenmore Square, Boston. One day this was replaced, too, for several days, by a genuine ice box.

The ice box lived in the garage. It was a sturdy wooden cabinet with two compartments. The upper compartment opened by flipping the top backward, exposing a tin liner with a hole in the centre connected to a narrow drain pipe. This conveyed water from a melting block of ice to the exterior. The lower compartment had shelves for food that depended on cool air to not spoil.

The ice box was pressed back into service when, in 1960, hurricane Donna visited our part of Massachusetts, causing a power failure that lasted several days. After hauling it into the house we got into the car and drove to the home of Mr. Churchill, an elderly man with a prominent growth on his neck who was known generally as “the ice man.” He maintained a small ice house near a pond where in former years ice had been harvested each winter. We purchased a very large block of ice and brought it home. My father then placed it in the ice box using ice tongs, just like Mr. Churchill’s, that had hung for years on the wall of the garage. It worked well enough until power was restored, but I can appreciate why one might prefer an electric refrigerator.

I sometimes think of Jack’s replies to my cousin Jerry when I marvel at our new quiet and efficient refrigerator, “the best one we’ve ever had,” as we’re inclined to say. As for the vacuum cleaner, I suppose I detest it about as much as Jack must have hated those old wire or wicker carpet beaters.

Photo credits:

“File:Brant rock radio tower 1910.jpg,” Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Brant_rock_radio_tower_1910.jpg#:~:text=It%20is%20a%20415%20foot,identical%20station%20in%20Machrihanish%2C%20Scotland. Visited 7 October 2024.

John Brooks “Jack” Howard, Photograph of Jack Howard in his radio room, used in a brochure describing his talk “Radio: Its Past, Present and Future,” ca. 1915.

John Brooks “Jack” Howard, Photograph of an elegant couple in a covered buckboard carriage, a canoe cart in the background. Maine, US, ca. 1900-1905.

The sale of phone equipment was novel, as Bell only leased equipment in the United States. The Tropical American company was brought down during the extremely competitive period just prior to the expiration of Bell’s patents in 1892, following several legal challenges brought against the company by Western Electric.

See “Reginald Fessenden,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reginald_Fessenden, visited 7 October 2024.

See Jack Howard’s brief essay, Trouants Island, ed. John B. Howard, Substack (22 September 2024), https://substack.com/home/post/p-149238050.

Hi John, Your family stories take me back to my youth of the 30’s& 40’s. I was born in 1934 , my parents didn’t have a “pot to piss in”. A rented house, no running hot water, no bath tub, no phone ,no fridge, no vac, no washing machine, no electric toaster. A hand-me-down radio. But A warm home with three meals a day with love. And just 1.3 miles from Trouants Island and 5.5 miles from Brant Rock . In fact my wife and now my son lives on a portion of the land Fessenden made his radio broadcast from. So, I too can relate to the wonders of modern conveniences as they slowly came to our family after WW ll. Thank you, Ray. <wrayfreden.com>