Reflections on Bureaucracy and Daily Life in France

Whether French bureaucracy is truly onerous might depend on where you're coming from

Before moving to France I lived most of my life in the US, with a year abroad in Germany as a student, 30 years in academic and administrative roles in the U.S., then 13 years as a university administrator in Ireland, where I also became an Irish citizen. The comparative perspective in this essay derives from that experience.

Moving to Ireland from the U.S. in 2009 my family got a taste the kinds of bureaucratic processes one confronts when moving permanently to a new jurisdiction. Some issues were taken care of by our new employers—paperwork relating to working permits and visas and some of the moving logistics. But there remained many things, including all the other issues that involve some kind of public service in the country. Getting a PPS number (Personal Public Service number—the Irish equivalent of a Social Security number), applying for a Drugs Payment Scheme (DPS) card, etc. We even had to take driving lessons and pass a rigorous driving test to obtain driving licences (I failed my first road test). Then of course there were annual interactions with immigration to renew visas, the tax authority, the social welfare office, and more.

Visas and work permits aside, these are mostly normal things that have counterparts in the U.S.—it’s just that in the U.S. they come at you over the course of time and aren’t compressed into a relatively short transitional period. The biggest nuisance we faced as newcomers in Ireland was the full day it would take each year to renew our visas—sometimes it took three hours of queuing outside just to enter the building. And it got more expensive every year. We were naturalised as citizens after five years and one of the advantages thereafter was not having to make the dreaded annual trip to the Garda National Immigration Bureau (GNIB). Apart from this we found the bureaucratic systems in Ireland to be, if anything, simpler and easier to negotiate than their U.S. equivalents. Being citizens of an E.U. country also made our eventual transition to living in France in retirement easier than it would have been otherwise.

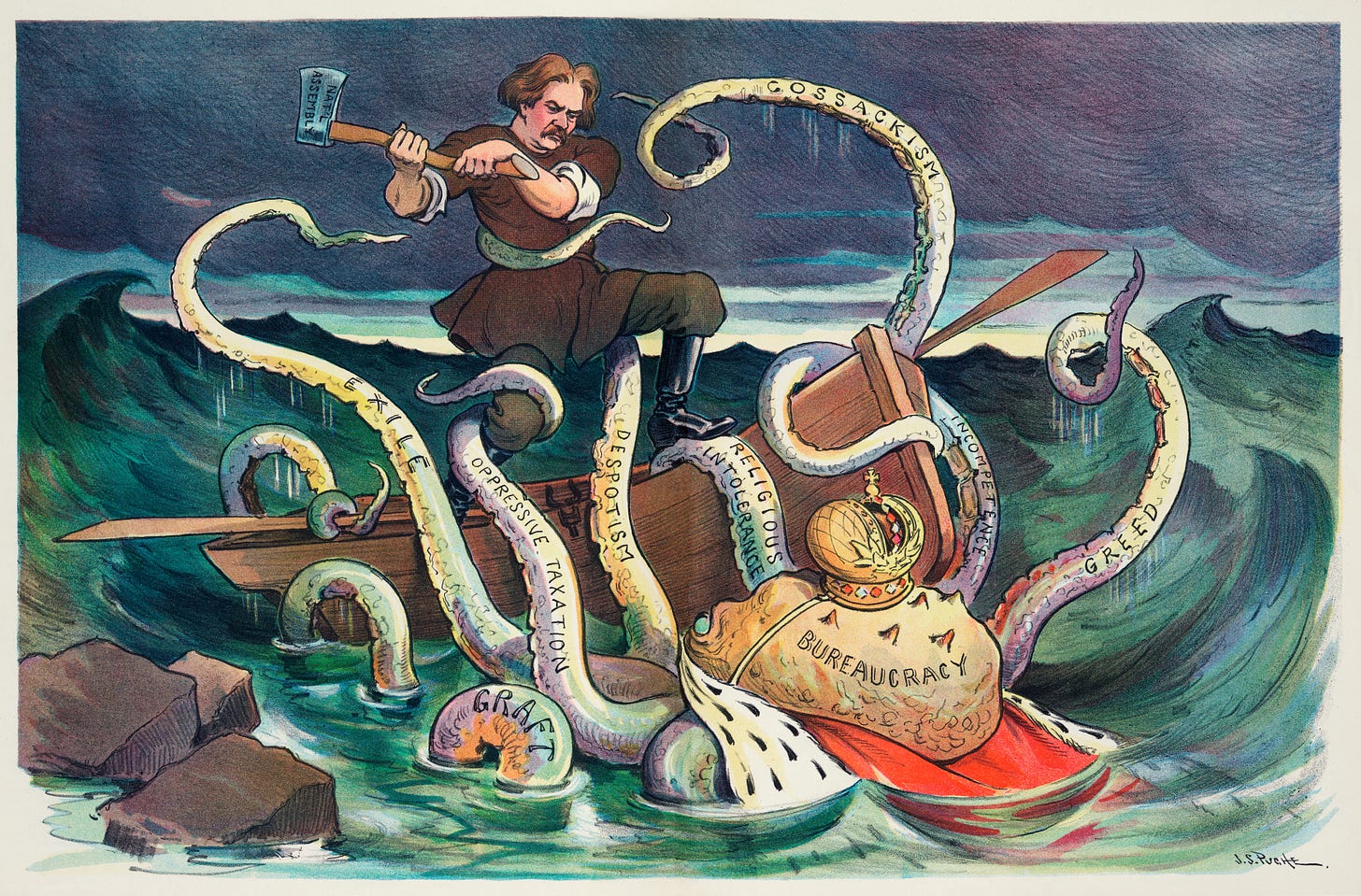

France has an undeniable reputation for having a demanding bureaucracy. Indeed, it is sometimes identified as the country that defined the modern bureaucratic state. French people embrace the stereotype and sometimes complain resignedly about it. Many expatriate commentators and consultants in the ever-growing move-to-France cottage industry also highlight this as both a necessary hurdle in moving to France from outside the European Union, and as a way of life thereafter.

But I’m happy to to say that the hype about oppressive French bureaucracy hasn’t lived up to its reputation, at least not for us.

I admit: part of this is because as a citizen of Ireland and therefore of the European Union we enjoy freedom of movement within the E.U.—we do not require special permission to live and work in France, so no need for visas or a carte de séjour. We do not plan to operate a business so there is no need for us to engage with the regulatory apparatus of commerce. We also qualify for the benefits of the national health insurance system, the Assurance Maladie, by simply transferring our health benefits in Ireland to France,1 accomplished by completing a standardised E.U. form (Form S1). Other than this our transition involved a minimum of government bureaucracy—all that comes to mind is the process of exchanging our Irish drivers licences for French ones.

Bureaucracy also exists in the private sector, of course, and settling in France involves managing a range of things that, again, have their American counterparts. In our case these involved leases, insurance policies (including our “top-up” insurance or mutuelles to cover the share of medical expenses not paid by the national health insurance framework—the Assurance Maladie), setting up contracts for utilities and phone service, etc.

The only truly difficult issue in this domain is the much-discussed challenge of obtaining a bank account. International banks are obligated to report to the IRS on the bank holdings of U.S. citizens (thanks to FATCA2) and on this basis private banks often refuse to open accounts for American citizens. (Think of this as a situation where public-sector American bureaucracy gets layered upon private-sector French bureaucracy.) Once you have identified a bank willing to accept you as a customer, the bank will also require of you a full disclosure of your income and assets. This invariably takes the uninitiated by surprise. (Some are also surprised that getting a loan from a bank can be nearly impossible without income sourced in France or a contrat de travail à durée indéterminée, or CDI.)

So yes, there are a number of bureaucratic processes to attend to when one transitions to France from another country. We did not find the transition significantly more challenging than moving to Ireland, other than the bank account issue (admitting again that we are E.U. citizens) and the processes of registering for health insurance. (It helps, by the way, that we came to France with a solid level B2 knowledge of French language.) But what about daily life once you’re established in France as a permanent resident?

Healthcare

Before speaking specifically about France, let me say that one of our nightmarish memories of life in the U.S. is how healthcare is administered. In retrospect, it might more accurately be characterised as a memory of experiencing healthcare as an industry, rather than as a public service.

We recollect the annual challenge of selecting an insurance plan from our employers’ offerings during the annual “benefits selection period”: trying to compare benefits, evaluating costs of premiums, deductibles, co-pays; understanding the in- and out-of-network providers; examining lists to see where our GP fit into things; etc. Then we recollect the healthcare consumer’s experience—especially the expenses and complexity of hospital billing with its medical codes, going to the pharmacy and not getting a prescription filled the same day because of a need to verify pre-approval of costs, and so forth. Then there are the inevitable “annual deductibles” and “co-pays.” I won’t even mention what happens when you contact an insurer’s customer service department. Talk about bureaucracy! And it is often bureaucracy that just doesn’t work or that leaves you high and dry with unforeseeable expenses.

In France, there is nothing comparable to the American process of choosing a major health insurance plan, or figuring out how things work in a system with so-called in- and out-of-network providers, etc. There is just the country’s universal health insurance system and the nationally regulated network of care providers. We can easily get an appointment with a GP, frequently on the same day; in some cases we can also make an appointment directly with a specialist physician without a GP’s letter attesting to the need for a specialist.

To pay, we produce our Carte Vitale—the card that shows entitlement to benefits from the national health insurance authority, the Assurance Maladie—and all or most of the cost of the visit is paid for (if a cash payment is required in addition, it will generally be reimbursed in part or in full within a week by one’s mutuelle). Drug payments are included—I’ve never paid anything for a prescription drug or other prescribed medical supplies in France. Dental and eye care is also covered by the Assurance Maladie. If you’re unfamiliar with the system you might assume it’s complicated, but in practice it’s not.3 It’s easy. It’s not stressful. And the costs of medical services and drugs is a fraction of what you would expect to pay in the U.S. anyway.

My opinion: Americans might take note that a government-administered single-payer system focused on serving the public can be more efficient, more effective, and far more beneficial to society that one whose priority is generating revenue for a handful of stockholders.

Taxes

First off, it’s important in leaving the U.S. for another jurisdiction to understand the terms of the applicable tax treaties, all of which are available in English from the IRS website.4 These are sometimes referred to as “totalization agreements,” the purpose of which is to relieve individuals from the burden of dual taxation. However they also define the terms by which tax is applied in other contexts as well—such as capital gains and inheritance. Read and understand the treaties: your tax accountant might not be familiar with them; most (remaining) IRS staff will not have committed their terms to memory either. This is not so much bureaucratic complexity as it is simply understanding the rules by which you live.

If you are working in France then there is both income tax and social charges (more about the latter below). All residents of France, including non-French nationals, must file an income tax declaration. French taxes (or more precisely, the rate which you are taxed) will be calculated on world-wide income, a practice followed by the IRS as well. The tax declaration itself is relatively simple and short, and after an initial year when the declaration must be filed manually, in printed format, they can be submitted electronically. That first tax declaration is filed after the first full year of residence in France. If you are working, the tax authority then calculates the a monthly income tax deduction for the next fiscal year based on the prior year’s income; reconciliation with actual income occurs when tax declarations are filed the following year.

Complexity occurs when someone who is resident in France receives income for work from a U.S. source. If the employer continues to declare you as a U.S. employee, then you would continue to pay into the U.S. Social Security system and be exempt from French social charges. Otherwise, if you work from home in France and receive U.S. income, you’ll pay income taxes in France and you will also have to arrange for payment of social charges. This is another example that comes not simply from the nature of French bureaucracy, but from the legal arrangements between two international jurisdictions regarding revenue and citizens’ fiscal obligations. (After arriving in France, I continued to work on a one-year post-retirement contract with an Irish employer; I paid income tax in France, but social charges were paid in Ireland.) Advice from an accountant specialising in cross-border taxation is essential to assure you meet all obligations—don’t expect the tax authorities to sort this out for you.

Part of the French tax declaration includes identifying world-wide financial accounts and assets, including trusts. Penalties for non-compliance or omissions can be stiff. Still, it is just a list so it lacks any kind of analytical complexity.

It puts things into perspective to consider what’s involved as a U.S. national living abroad in filing a U.S. income tax return. Especially once you become resident in a country outside of the U.S. and are faced with the complexities of understanding various tax concepts that domestic residents never encounter: Foreign Tax Credits (IRS Form 1116), the Treaty-Based Return Position Disclosure (IRS Form 8833), the Foreign Earned Income Exclusion,5 and FinCEN Report 114, Report of Foreign Bank and Financial Accounts (“FBAR”).6 (A Residency-Based Taxation Bill is currently being considered by the Joint Committee on Taxation of the U.S. Congress which would alleviate much of this burden; see the Democrats Abroad explainer on this issue.) You also have to declare any foreign bank balances over the equivalent of USD $10,000 during the tax year, and report how many days you have spent in the United States during that year as well (this relates to the IRS’s “substantial presence test”—an important if easily overlooked detail7).

So in the competition for the more complex bureaucratic processes, the U.S. wins the income tax match hands down. If you move to France and continue to work, you will inevitably have to deal with filing taxes in two jurisdictions. If you come to France for retirement from the U.S. (and some E.U. countries), your income might be fully exempt from French taxes, but you’ll have to file a déclaration des revenus in France anyway. As for other kinds of taxes, the main concern would be property tax, whether for a full- or part-time residence, or a property rented to third parties. These are generally similar to U.S. property taxes. (Habitation tax on rented properties in France has been phased out.) But once again—don’t fail to pay attention to the French droits de succession, or inheritance tax regulations.

I mentioned “social charges” above, which can be a source of confusion for those coming to France from outside the E.U.. “Social charges” is a catch-all phrase that refers to various kinds of charges that support, in France, one of the world’s most comprehensive social security systems, which covers “universal state healthcare, some of the highest state pensions in Europe, generous maternity, paternity, childcare, and family benefits, and protections for long-term illness, disability, and unemployment.”8

Social charges are paid by both individuals and employers; individuals can deduct their payments for social charges from their income in their annual income tax declaration; as a result about half of French households pay no income tax at all. If you are a U.S. citizen and your income is sourced from a U.S. business that does not declare you as a U.S. employee, then arrangements must be made for payment of social charges in France—something to discuss with your international tax account and your employer (who would then not deduct U.S. Social Security payments from your pay).

Note that retired U.S. citizens resident in France who earn U.S. Social Security, or other retirement income from investments recognised as such by the IRS—such as a 401(k)—pay taxes on that income only in the U.S. as per the tax treaty between the two countries.

I could go on comparing other things, but in most cases I’d say the remaining bureaucratic requirements in the U.S. are similar to those in France. These would be such things as: securing a loan for buying property or a car (expect difficulty if your income is not sourced in France, or if you do not have a CDI); car inspections; drawing up a will (though French laws of succession are considerably different from those in most U.S. states, other than Louisiana); arranging for children’s education; etc.9 The issue of the costs of higher education and student loans is a special case; I’ve written separately about this here and here.

For me, being settled in France without the burden of acquiring and maintaining visas and a carte de séjour, life is easier and the bureaucratic requirements in most cases no more complex than the parallel processes in the U.S. Ultimately there are two big areas where the U.S. has incontestably more complex bureaucratic systems:

Filing one’s annual income tax declaration is definitely easier in France; many, perhaps most, French residents do not seek the assistance of a tax accountant in doing so. (I’d not recommend filing a U.S. tax return as a U.S. resident in France without the advice of a tax professional experienced with international clients, at least in the first year of residency.)

In the case of healthcare, there really is no comparison: managing one’s health in France is largely without the bureaucratic and financial burden of negotiating the arcane healthcare framework in the U.S. The lack of complexity, low cost and the personal security it provides is priceless. It’s such a relief. And for me and my family, that makes all the difference.

So is French bureaucracy as onerous as its reputation suggests? If your base point of reference is the United States and you focus on the big issues of taxes and healthcare, then I’d have to say no. If you operate a business, engage in cross-border employment, or have to regularly deal with immigration authorities due to visa issues, you might feel differently. Just understand that, in living outside of your home jurisdiction, you are not trading one bureaucracy for another; you now get to deal with two (or as in my case, three).

Note that the entitlement to health benefits is not awarded simply by becoming an Irish citizen. Rather those rights are accrued through contributions to a Social Insurance Fund by an employer (or an employer and from the worker’s earnings), called Pay Related Social Insurance (PRSI). See “Credited social Insurance contributions” https://www.citizensinformation.ie/en/social-welfare/irish-social-welfare-system/social-insurance-prsi/credited-social-insurance-contributions/.

“Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA),” Internal Revenue Service (4 Dec 2024) https://www.irs.gov/businesses/corporations/foreign-account-tax-compliance-act-fatca (consulted 28 Dec 2024)

See the summary of the French healthcare system by David Lebovitz “Down for the Count: A few notes on the French health care system,” David Lebovitz Newsletter (18 Mar 2024) https://davidlebovitz.substack.com/p/down-for-the-count (consulted 28 Dec 2024)

“United States income tax treaties - A to Z,” Internal Revenue Service (19 Nov 2024) https://www.irs.gov/businesses/international-businesses/united-states-income-tax-treaties-a-to-z (consulted 28 Dec 2024)

“Foreign earned income exclusion,” Internal Revenue Service (22 Aug 2024) https://www.irs.gov/individuals/international-taxpayers/foreign-earned-income-exclusion (consulted 28 Dec 2024)

“U.S. citizens and residents abroad – Filing requirements,” Internal Revenue Service (19 Aug 2024) https://www.irs.gov/individuals/international-taxpayers/us-citizens-and-residents-abroad-filing-requirements (consulted 28 Dec 2024)

See "Substantial presence test,” Internal Revenue Service (22 Aug 2024) https://www.irs.gov/individuals/international-taxpayers/substantial-presence-test#:~:text=183%20days%20during%20the%203,before%20the%20current%20year%2C%20and (consulted 29 December 2024). The IRS is wary of U.S. persons fraudulently declaring foreign residency to avoid U.S. taxes and may need to be convinced that someone who has moved abroad is, in fact, a bona fide resident of a new jurisdiction—even if one has clearly become tax resident in that new location. For example, if you spend 31 days or more in the U.S. during the first year you are fiscally resident outside the U.S., you might be seen to fail the “substantial presence test” and be held responsible for income tax in two countries. The only way to prove your bona fides is then to defer paying income tax until a future year, by which time your legitimacy as a foreign resident has become undeniable.

“What You Need to Know About French Social Charges,” FrenchEntrée (5 Apr 2022; updated 1 Apr 2024) https://www.frenchentree.com/living-in-france/what-you-need-to-know-about-french-social-charges/ (consulted 28 Dec 2024)

One caveat is that French society is much less reliant upon credit than American society. Credit cards are unknown, and there is nothing like a national credit agency that computes “credit scores” as in the U.S. This doesn’t imply additional bureaucracy, but perhaps it means there is less of it. If your income is not sourced in France, or if you work in France without a “contract of indefinite duration” (a “CID”), getting a loan of any kind can be very difficult: be prepared to pay in cash.

Excellent article, John. Very straightforward and factual, without the hysterics.

Thanks Clarice.