It doesn't have to be this way - U.S. Healthcare

A perspective from an American living in France

I left the United States with family in 2009 to assure the availability of reliable, quality and affordable healthcare regardless of prior medical history and pre-existing conditions. For many Americans, in the days before passage of the Affordable Care Act in 2010, the prohibition of insurance to those with chronic illness was an existential issue. Our response was to move to a jurisdiction where healthcare was not based on having been privileged by good health and full-time employability. We were fortunate to be in a position to do this, professionally and financially. We moved to Ireland for work, then moved to France for retirement at the start of 2022.

As many expatriate Americans would tell you, moving abroad does not disconnect you from American culture nor from its policies and bureaucratic procedures. It is also, for many, impossible to simply stop caring about the nature and state of American society, or to truly feel like one is no longer a part of it. It is always there, and social upheavals and tragic events in the U.S. cause as much distress and worry as they ever did.

Part of the reason for this is, perhaps paradoxically, that in other jurisdictions many of the stressors of American life have no real counterpart. I’m thinking about mass shootings and gun violence in general, medical debt and the costs of healthcare and insurance, student loan debt, credit card debt, school lunch debt (!), the costly corporate privatisation of nearly everything (such as housing and traditional municipal services), the constant degradation and coarseness of public political discourse, etc. When you live in a place where these concerns are not a part of daily life, you realise:

It doesn’t have to be this way.

Even after fifteen years of living apart, all the above issues continue to cause us distress. Partly it is because we worry about family and friends who remain in America. In part, too, it is because with the passage of time we realise that, for us, there is no obvious path to returning to America. Too much has changed culturally, and too little has changed (for the better) specifically in the critical domain of healthcare and health insurance. That’s what I want to write about today.

I’m a retiree, so I’ll focus, for the moment and for the sake of brevity, on an aspect of American healthcare that serves my age demographic: Medicare.

Recently I’ve had to refresh my understanding of Medicare as an older relative in the U.S. has required intensive medical care. As U.S. citizens over 65 my wife and I are beneficiaries of Medicare, at least in theory—we live outside of the country and therefore only subscribe to basic Medicare (covering in-patient hospital services), and benefits are only available within the U.S. Not being an active user I had forgotten some of the fine details of the Medicare programme; indeed there have been changes I’ve not kept up with over the past several years. However, the government’s official Medicare website provides comprehensive and up-to-date information.

Medicare compartmentalises the expenses associated with medical care, in broad strokes, by industry. Medicare A and B focus, respectively, on hospital in-patient care and all other forms of direct medical care; Part D on prescription drugs. Taken together, these programmes are now referred to as Original Medicare by the programme administrators.

There is also Medicare Part C, better known perhaps as Medicare Advantage.1 The Medicare.gov website describes the programme as a “Medicare-approved plan from a private company that offers an alternative to Original Medicare for your health coverage. These ‘bundled’ plans include Part A, Part B, and usually Part D. Plans may offer some extra benefits that Original Medicare doesn’t.” In describing the differences between Original Medicare and Medicare Advantage, the following points stand out:

In many cases, you can only use doctors who are in the plan’s network.

In many cases, you may need to get approval from your plan before it covers certain drugs or services.

Plans often have different out-of-pocket costs than Original Medicare or supplemental coverage like Medigap. You may also have an additional premium.

Oddly the official Medicare website fails to mention that subscribers to Medicare Advantage plans are disallowed from also purchasing Medigap coverage (see below). There are other things to be aware of, too, and reasons to be cautious—including signs of a realisation that Medicare Advantage has fallen short of expectations of consumers, care givers, the U.S. Congress, and even Wall Street.2 Nevertheless some 54 percent of subscribers register for Medicare Advantage rather than Original Medicare.3

There is, in addition, a standardised private insurance plan that makes up for some of the expenses not covered by the Original Medicare programme. It is called Medigap. I am familiar with this since entitlement to a discount when enrolling in such a programme is one of the benefits awarded to me as a retiree from a US employer. Again, it is not available to participants in a Medicare Advantage insurance programme.

Evaluating what financial protections are provided by a Medicare insurance package brings home just how difficult it is to differentiate what a suite of public and private insurance programmes cover and what an individual’s out-of-pocket expenses for healthcare actually turn out to be. I won’t go through this in further detail, but instead I invite the reader to visit Medicare’s own website to review how much the consumer pays under the various conditions described under Original Medicare. (Obviously I can refer to no such summary for all the Medicare Advantage plans available.)

Just to make the situation more complex, the administration of Medicare Part D is also subject in most cases to the decision-making of “pharmacy benefit managers,” or P.B.M.s. In a recent New York Times report,4 P.B.M.s are identified as middlemen who work on behalf of public- and private-sector entities to manage prescription drug benefits, and who “have been systematically underpaying small pharmacies, helping to drive hundreds out of business.” The beneficiaries of this activity are the handful of companies that process all but about 20 percent of drug prescriptions in the U.S. (and are coincidentally the parent companies of the P.B.M.s), allowing them to gain an ever greater share of the lucrative prescription drug market.5 Even so, it seems that’s not enough to satisfy some healthcare companies’ stockholders.6

If you have a prescription for medicines that treat a chronic illness, you might have had the experience of visiting your pharmacy to renew the prescription, only to be advised that the medicine cannot be issued immediately because coverage needs to be verified with the insurer or, more likely, the insurer’s agent (a P.B.M.). The same kind of experience can be had when transitioning from hospital care to a rehabilitation or nursing facility, where insurer’s approval (including approval from Medicare) can require days. These bureaucratic procedures are undertaken to validate coverage for specific expenses and, in effect, to protect corporate profits, but can delay timely delivery of medicines and services.

For the consumer there is also the matter of sorting out the invoices that arise from medical care. In this context a different kind of medical professional, particularly for hospital care, is likely to play a role: the medical coding professional. The American Academy of Professional Coders defines medical coding as “the transformation of healthcare diagnosis, procedures, medical services, and equipment into universal medical alphanumeric codes. The diagnoses and procedure codes are taken from medical record documentation, such as transcription of physician's notes, laboratory and radiologic results, etc.”7 In other words, the application of medical codes is the interpretation of information expressed in natural language into a system of codes generally useful only to those involved in the financial/insurance side of healthcare. The interpretations can determine whether a lower or higher cost is attributed to a medical intervention or whether coverage applies at all, and this has opened their application to abuse.8 It is often the medical coding, rather than the language of the direct care providers, that one sees on the invoices. In other words, medical billing, through its language, generally prioritises the interests of insurers over individual patients.

Another matter that makes understanding expenses for medical care challenging is the delegation of clinical services to businesses outside of the hospital or clinic where direct care is provided, including across state boundaries. Hospitals and clinics can choose to outsource services for radiology, clinical laboratory testing, patient transportation, etc., to specialised companies operating their business functions in locations distant from the facility where direct care is given. This in itself can be confusing when an invoice is received by the patient from a hitherto unknown company with which they have had no direct contact. Combine it with the opaque alphanumeric codes used to identify specific expenses, and consumers’ ability to comprehend medical bills becomes extremely challenging. Such confusion can also create a risk of paying inflated or completely inappropriate sums for services received, or perhaps not received at all.

The activity of P.B.M.s and medical coders obviously applies to healthcare in the U.S. in general, not just Medicare, to which about 19 percent of Americans with health insurance subscribed.9 There are other challenging complexities with another other major government-sponsored healthcare programme, Medicaid, which serves another 19 percent of Americans. And of course there are the various other kinds of private health insurance that count around 55 percent of Americans as customers.10

With reference to health insurance issues in general, I should mention some additional foibles of actual healthcare administration which include practices that citizens likely accept as simply “the way things are.” Consider of concept of an annual enrolment period for insurance plan subscriptions; the accompanying annual changes in scope and costs of health plans that require consumer analysis and decision-making; in-network and out-of-network practitioners and institutions; deductibles; and expenses shared by percentage. Even the Affordable Care Act introduces new administrative processes and virtual infrastructure that can be challenging for insurance customers.

Finally reflect on the crushing burden of medical debt felt by citizens in the United States. According to the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2017 Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP), 19 percent of American households had medical debt at that time.11 By 2021 the aggregate debt total was a staggering US $220 billion.12 And a significant proportion of personal bankruptcies in the U.S.—around 40 percent—are due primarily to medical debt.13

When the American way of managing healthcare is all you know, it is easy enough to assume that it simply is the way it is and the way it has to be. But really, it doesn’t have to be this way. I know this from personal experience.

For example. Last week, here in France, I experienced a minor health issue in the morning. I was able to make a noon-time appointment with my general practitioner for a consultation (standard charge is €25 without insurance, but cost to me is zero). I received a prescription for laboratory tests, which were done immediately (no cost to me), and I fulfilled a drug prescription as well (no cost for that, either; over-the-counter cost in the US would have been $382). The ease of obtaining and paying for these services is made possible by the linkages provided through a single-payer entity, the French Assurance Maladie—the healthcare division of the French Social Security system. More complex medical issues involving hospitalisation are accompanied by similarly straight-forward billing; again I speak from experience.

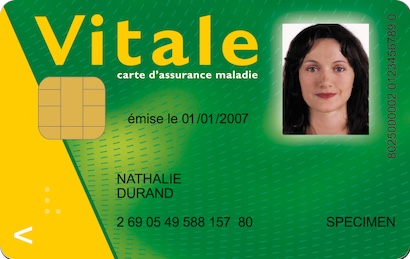

Ask any French person about French bureaucracy, and they will echo the stereotypes heard around the world about bureaucratic complexity and paperwork in France. But the Assurance Maladie is as consumer friendly as such a programme can be. It does not cover all insurance costs, nor does it fully regulate what medical providers can charge, but making use of it is simplicity itself. One produces one’s Carte Vitale (a plastic card the size of a credit card), and the financial transaction is almost complete. I say almost because it is expected that residents contribute a share of the already comparatively low medical costs. A provider might require payment for that share from the patient, subject to reimbursement in full or in part by the Assurance Maladie and a patient’s low-cost private “top-up” insurance, called a mutuelle. Reimbursements are generally made within two weeks. It is also the case that if an individual has been certified as having an “affection de longue durée,” i.e., a long-term illness (such as epilepsy, hepatitis B or C, etc.), most healthcare charges are waived entirely.14 (David Lebovitz provides an excellent summary of how the Assurance Maladie functions if you wish to read further about it.)

Whenever I hand my Carte Vitale to one of my care providers, he holds it up before me and says “this is the best thing ever invented in France.” I have never contradicted him.

So, an example from at least one European jurisdiction suggests that the healthcare experience of Americans does not have to be the way it is. At least conceptually.

My worry is, now as it was fifteen years ago, that in the U.S., the complexities of healthcare administration and delivery, the extraordinary amounts of money involved, the power of the corporations and individuals who benefit most from these sums, and the unpredictability of U.S. government policy-making in general, means that it just may not be possible to change the American approach to healthcare through through any conventional democratic means.

Medicare for all? A nice concept. For my fellow Americans I wish it could be—after all, I’ve had a sense of how it changes one’s quality of life by living in countries where similarly conceived programmes exist. But I am sadly coming to believe that another insurance concept would have to be realised for it to happen in the United States: an “Act of God.”

See “Understanding Medicare Advantage Plans”

https://www.medicare.gov/publications/12026-understanding-medicare-advantage-plans.pdf (consulted 13 November 2024).

See the following: Aaron, D.G., Cohen, I.G. & Adashi, E.Y. “Medicare Advantage Under Fire: Public Criticism and Implications,” J GEN INTERN MED 39, 2849–2852 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-024-08876-7 (consulted 16 November 2024) ;

Wendell Potter, “America’s Seniors Are About to Pay a High Price for Wall Street’s Growing Disenchantment with Medicare Advantage,” HEALTH CARE un-covered (8 August 2024) https://healthcareuncovered.substack.com/p/americas-seniors-are-about-to-pay (consulted 15 November 2024) ;

Trudy Lieberman, “Hospitals across the country are dumping Medicare Advantage plans and canceling their contracts with insurers,” HEALTH CARE un-covered https://healthcareuncovered.substack.com/p/hospitals-across-the-country-are (7 December 2023) ;

and Trudy Lieberman, “A Daughter’s Fight to Protect Her Parents from Costly Pitfalls of Medicare Advantage“, HEALTH CARE un-covered https://healthcareuncovered.substack.com/p/a-daughters-fight-to-protect-her?r=1u1uw5&utm_medium=ios&triedRedirect=true (consulted 13 November 2024)

Meredith Freed, Jeannie Fuglesten Biniek, Anthony Damico, and Tricia Neuman, “ “Medicare Advantage in 2024: Enrollment Update and Key Trends,” KFF https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/medicare-advantage-in-2024-enrollment-update-and-key-trends/ (consulted 16 November 2024)

Reed Abelson and Rebecca Robbins, “The Powerful Companies Driving Local Drugstores Out of Business,” New York Times (19 October 2024) https://www.nytimes.com/2024/10/19/business/drugstores-closing-pbm-pharmacy.html?smid=url-share (consulted 13 November 2024)

United States House Committee on Oversight and Accountability, “The Role of Pharmacy Benefit Managers in Prescription Drug Markets” (9 July 2024) https://oversight.house.gov/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/PBM-Report-FINAL-with-Redactions.pdf. This report observes that “the three largest PBMs, CVS Caremark (Caremark), Cigna Express Scripts (Express Scripts), and UnitedHealth Group’s Optum Rx (Optum Rx), control more than 80 percent of the market and are vertically integrated with health insurers, pharmacies, and providers.” It also states: “As large health care conglomerates, some have argued that these PBMs’ vertical integration with insurers and pharmacies would better position them to improve patient access and decrease the cost of prescription drugs.3 Instead, the opposite has occurred: patients are seeing significantly higher costs with fewer choices and worse care.”

Danielle Kaye, “CVS Ousts C.E.O. as Sluggish Growth Spooks Investors,” New York Times (18 October 2024) https://www.nytimes.com/2024/10/18/business/cvs-ceo-karen-lynch.html?smid=url-share (consulted 13 November 2024)

Former CVS CEO Karen Lynch has since been replaced by David Joyner, who has appointed Steve Nelson to head Aetna, CVS’s managed healthcare subsidiary. For a perspective on the implications of this appointment see Wendell Potter, “Leadership Shift at CVS/Aetna: Familiar Faces, Familiar Tactics, and Why Patients Will Pay the Price,” HEALTH CARE un-covered https://substack.com/home/post/p-151824320 (18 November 2024)

“What is Medical Coding,” AAPC (undated) https://www.aapc.com/resources/what-is-medical-coding (consulted 15 November 2024)

Elisabeth Rosenthal, “Those Indecipherable Medical Bills? They’re One Reason Health Care Costs So Much,” New York Times (29 March 2017) https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/29/magazine/those-indecipherable-medical-bills-theyre-one-reason-health-care-costs-so-much.html (consulted 15 November 2024)

Preeti Vankar, “Percentage of U.S. Americans covered by Medicare 1990-2023,” Statista (22 October 2024) https://www.statista.com/statistics/200962/percentage-of-americans-covered-by-medicare/#:~:text=Medicare%20is%20an%20important%20public,aged%2065%20years%20and%20older (consulted 13 November 2024)

Katherine Keisler-Starkey, Lisa N. Bunch, and Rachel A. Lindstrom, “Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2022,” United States Census Bureau, Report Number P60-281 (12 September 2023) https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2023/demo/p60-281.html#:~:text=Of%20the%20subtypes%20of%20health,percent)%2C%20and%20VA%20and%20CHAMPVA (consulted 13 November 2024). “Of the subtypes of health insurance coverage, employment-based insurance was the most common, covering 54.5 percent of the population for some or all of the calendar year, followed by Medicaid (18.8 percent), Medicare (18.7 percent), direct-purchase coverage (9.9 percent), TRICARE (2.4 percent), and VA and CHAMPVA coverage (1.0 percent).”

Neil Bennett, Jonathan Eggleston, Laryssa Mykyta and Briana Sullivan, “19% of U.S. Households Could Not Afford to Pay for Medical Care Right Away,” United States Census Bureau (7 April 2021) https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/04/who-had-medical-debt-in-united-states.html (consulted 13 November 2024)

Shameek Rakshit, Matthew Rae, Gary Claxton, Krutika Amin, and Cynthia Cox, “The Burden of Medical Debt in the United States,” KFF (12 February 2024) https://www.kff.org/health-costs/issue-brief/the-burden-of-medical-debt-in-the-united-states/#:~:text=This%20analysis%20of%20government%20data,debt%20of%20more%20than%20%2410%2C000 (consulted 13 November 2024)

David U Himmelstein, Robert M Lawless, Deborah Thorne, Pamela Foohey, Steffie Woolhandler, “Medical Bankruptcy: Still Common Despite the Affordable Care Act,” American Journal of Public Health (ajph) (March 2019) doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304901 (consulted 13 November 2024)

Assurance Maladie, “Qu’est-ce que le dispositif appelé Affection Longue Durée (ALD) ?” (28 May 2024) https://www.ameli.fr/alpes-maritimes/assure/droits-demarches/maladie-accident-hospitalisation/affection-longue-duree-ald/affection-longue-duree-maladie-chronique (consulted 16 November 2024)

Thank you for stating the obvious so clearly. I agree that we won’t have Medicare for All, or anything else for the common people through the democratic process that has been bought over the past several decades. That is why my first article in my substack is about how we organized a “shit hole” nursing home. Healthcare will have to be revolutionized in the U.S. by its practioners supported by the recipients of care.

I always look for the underlying cause of a problem. The following book recommendation is truly a deep dive in that direction. “The Goodness Paradox” by Richard Wrangham. If you don’t have time to read the book, the review by Ronald J. Planer gives a good overview. The idea that interested me most was that humans living in bands or small groups self-domesticated. We don’t seem to have way forward in the modern world to continue along that evolutionary path, in my opinion. Maybe the alph males will eliminate each other.

I”m going to write more on my experience as a patient because I am hoping some practitioners will see themselves from my perspective as a long-suffering patient who was a mother, wife, nurse, and human being. You wouldn’t understand how many doctors and nurses shut off their feelings and begin to see the patient as the enemy, especially those they didn’t heal and keep returning. Moral injury either causes the practitioner to withdraw emotionally, remain vulnerable and acquire chronic mental and physical diseases, or leave. Another path would be to join with others to change the system.

It’s been said that the U.S. is now like Germany in the 1920s and 30s. I see the similarity in that the Germans were being drained of their resources due to war reparations, while we are being drained of our assets through what the economist, Michael Hudson, calls the F.I.R.E. economy, (finance, insurance, and real estate.)

Private equity has drained the assets of the industry that remained in the U.S. and now are draining the assets of hospital systems. Hudson’s book, “Killing the Host” explains. The confused population that struggles to survive and retain civilized family life doesn’t know where to turn, just like the Germans who also chose the wrong direction.

Thanks again and I hope you don’t mind if I copy your essay for a reference. I hope you and your family continue to stay well.