Duxbury Days and the 4th of July

Three days of surreal small-town amusement to celebrate the nation's birthday

I grew up, through age 12, in a small town on the South Shore of Massachusetts called Duxbury. At the time it was quite rural and, in the part of town where my family lived, there were several working farms. Indeed, the centre of neighbourhood activity was the Grange Hall, just up the street from our family home. There were often gatherings there of people from the “Crooked Lane” neighbourhood—the name for the area where we lived—for dinners on special occasions. And there was a weekly “Whist Party” advertised on a sign in front of the building.

When July 4th approached, however, nobody wanted to be inside—there was too much going on in town as it celebrated the annual “Duxbury Days” festival—an event that had been observed for decades. By the time of my childhood, it had achieved a predictable form with three key events:

A carnival: This was a kind of fair with mechanised rides such as ferris wheels, cups-and-saucers, and my favourite ride, called “The Octopus.” And there were also various sideshows and tents where prizes could be won by accomplishing some trivial but sometimes challenging feat.

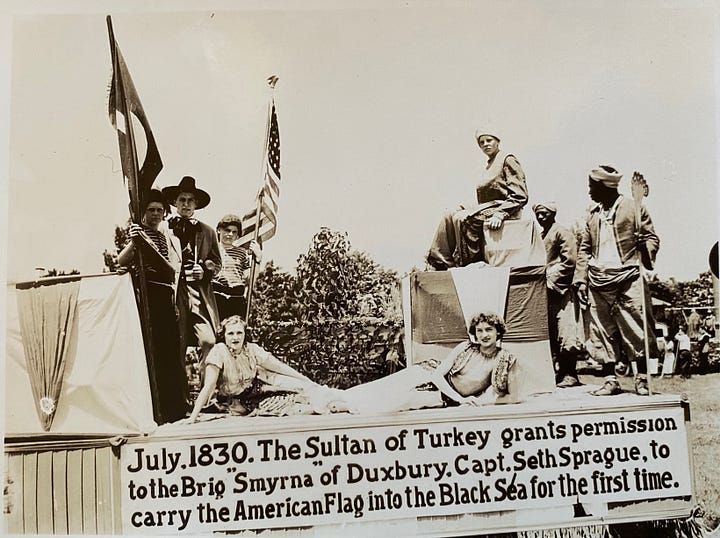

A parade: The parade also had a more-or-less canonical form familiar to residents of many New England towns: marching bands; Shriners in their red Fez’s darting here and there in tiny automobiles; fire engines; marching policemen; etc. The most memorable to me are “the horribles”—old junk cars or parade floats that were, well, an exercise in poor taste. My most vivid memory is of a float bearing a man seated on a gold-painted toilet, waving to the crowd and wearing a crown. How prescient!

A bonfire. This always took place at night, and my parents were never eager to expose their children to this spectacle; I remember seeing it only once.

Carnival

The carnival was a little different each year. Looking back, there were aspects of it that were truly bizarre.

One year there was a spectacle featuring a man (clearly a seasoned carnival huckster), a motorcycle, and a monkey named “Sparky.” My recollections are not detailed, but were reinforced by shared recollections of the event by family members in the years after. The man was a stereotypical carny-person; he would would attract a crowd in circus-barker fashion, speaking about the never-before-seen phenomenon of a motorcycle-riding monkey. Expectations could only be raised so far, though, since the “motorcycle” was little more than the kind of motorised mini-bike that most boys my age would have loved to have owned, and the course for the motorcycle was limited to a rather small circle.

Once the size of the crowd of onlookers had grown to a satisfactory level the show began. The “motorcycle” was started—it was very loud—and a very reluctant small monkey was chained to its seat. As the monkey struggled and screeched the huckster called out “I know you’re eager to ride, Sparky!” then reached out with a pole, tripping a switch on the “motorcycle” that caused it to start moving. Round-and-round it went, the terrified monkey’s screams creating an awful counterpoint to the lawn-mower like roar of the engine. I think most people watching were in a state of horror; my father, a genuine animal lover, seemed traumatised watching the abuse unfold in front of us. He spoke about the cruelty of it for years afterward. Eventually the huckster reached out and cut the engine just as he’d started it, and proceeded to solicit contributions from the quickly dispersing crowd of onlookers.

There were also various side-shows, most of which featured strange sights that were easily recognised as scams even before visiting them. There was a tent advertising a woman with a body of a snake; another featured “the woman with an iron tongue,” who was depicted in a poster wherein a metal weight, labelled “200 lbs.,” hung suspended on a wire from a hook in the woman’s tongue. My companions and I never feel for such nonsense—we saved our money for a much larger show put on by an entertainer called “The Indian Fakir.”

Inside the tent there was a raised platform for the entertainers, who were three: the “Fakir,” who dressed in a costume evocative of … somewhere faraway; a woman dressed in a sparkling bathing suit and high heels; and a portly middle-aged man identified as “The Human Pin-Cushion.” The Fakir (which at the time I understood to be the “Faker," an appellation that would have fit equally well), acted as master of ceremonies, introducing each new episode of the entertainment. My companions and I huddled at the edge of the platform where we could see things up close.

As I recall it all started with The Human Pin-Cushion. True to his title, he began by producing a long steel needle, holding it aloft and waving it about for all to see. He then wiped a part of his arm with alcohol and proceed to push the needle through his arm until it emerged on the other side, whereupon he dropped his hand to pull it completely through. There were many anguished sounds arising from the crowd as this took place, and afterward as he showed a line of blood on his arm, which he dispatched with the swipe of a cotton ball.

As if this were not enough, he then proceeded to produce a very long nail—I no longer remember how he introduced this part of his act—and pushed it partially into a nostril. This was enough to cause much cringing among us boys, and the others as well. But he then picked up a hammer and began to tap the head of the nail, until the nail had almost disappeared. There were muffled cries with each tap of the hammer. Now, I do recall exactly Mr. Pin-Cushion’s words as he removed the nail. He said, “Oh look there’s blood!” Then, inspecting it more closely, he turned to the audience and announced, “No, it’s snot.” Again, many cries representing mixed emotions from the audience.

The Fakir took the stage to perform several parlour tricks that were familiar from other magic shows of the time. One of these involved a device sometimes called a “hand guillotine,” an apparatus with an opening through which one could thrust one’s arm (or, alternatively, a piece of fruit or vegetable), and an articulated blade that descended across the space where the hand (or vegetable) was secured. This was a larger-than-usual version of the device, capable of accommodating a small cabbage or butternut squash. These vegetables were used to demonstrate the deadly efficiency of the “guillotine,” which easily sliced through them. But this was just the introductory phase of the act.

The Fakir turned to the audience and called for volunteers to come to the stage. Standing next to me was my neighbour, a boy my age—we’ll call him “Brian”—who responded eagerly and clambered up onto the platform. Now Brian was a small but relatively fearless lad; he also had what one might call a speech disorder. He lisped, and had difficulty with the letter “R,” and sometimes struggled through words with several consonants. As I recall he used to call English muffins “Inglo nuffins.” My guess is, had he been able to anticipate what came next, he might have chosen not to raise his hand.

Once Brian was on the stage, the Fakir began to speak to the audience about the dangers inherent in what what about to take place. To relieve himself of responsibility for any injury that might be sustained, he announced that his youthful volunteer would have to recite a statement absolving all liability for what might happen. I recall the words spoken verbatim, since they were repeated frequently thereafter by family members who were in attendance:

I am going to allow this prestidigitator to sever my cranium from the rest of my anatomy.

This was spoken with pregnant pauses between each segment of the sentence to allow Brian to repeat it. It was off to a very bad start when Brian reached “prestidigitator”—a word he surely had never heard before and whose meaning was surely unknown to him. He just could not pronounce it—struggling through it syllable by syllable, starting over repeatedly, then finally being prompted to continue on to the next unfamiliar word, “cranium,” which took a few attempts, then “anatomy,” which took some doing as well. Once the words were spoken the inevitable took place—Brian’s arm (not his “cranium”) passed through the opening in the guillotine and amazingly survived the descent of the blade.

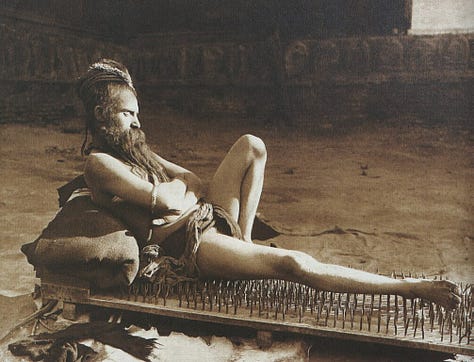

Either before or after—I no longer remember—the Fakir also lay upon a “bed of nails.” This was a board through which had been pounded MANY long nails. They had been arranged in so dense a manner that very little space existed between them. None of us were impressed when he lay on the “bed,” even when afterward he turned his back to the audience to allow us to see the pattern made by the nails in his skin. We were even more disappointed that he did not carry out some of the tricks depicted on the posters outside the tent—such as sword-swallowing and fire-eating.

At this point during the performance an “electric chair” was pulled out onto the stage and was joined by the young woman in the bathing costume. The Fakir announced that she had the singular talent of being able endure the deadly high voltage shock of the electric chair, which he called “Old Sparky” after the actual electric chair in the state’s Walpole State Prison. When she sat in it, the Fakir fastened wrist straps to hold her in place. The switch that activated the flow of electric current was mounted on a board—it was one of those menacing-looking double-pole knife-switches, the kind you might have seen in a Frankenstein film. The Fakir stepped forward and threw the switch.

At first nothing changed. But then the Fakir produced a light bulb and, placing it in the woman’s mouth, it illuminated! Obvious even to a child that there was some fakir–y involved. This was followed by an equally unconvincing trick—the poor woman in the electric chair stuck out her tongue, and the Fakir ostentatiously touched to it a wooden match—which burst into fire!

There might have been more, but what I remember better was what happened after she was released from Old Sparky (not the motorcycle-riding monkey, but the chair). The Fakir made a dramatic plea on her behalf. He explained that it had been her childhood dream to be a part of the circus and had run away from home to realise her dream. The Fakir, it seems, had taken her in but did not have the means to pay her—she had remained simply due to her extraordinary passion for pursuing this profession. (I cannot imagine the outrage this whole scene might engender if this scenario played out in front of a current-day audience.) So, inevitably, the speech ended with a plea for contributions.

Once again being in the front row of spectators proved to be a disadvantage, as we were called upon to mount the stage and contribute by dropping money into a waiting container. I stayed put, but my older brother and another boy the same age as he ascended the couple steps to the platform, whereupon one of them—I don’t recall which—dropped a single penny into the receptacle. The Fakir was not about to let this affront pass unnoticed.

He stepped forward blocking the path to exit the platform, bellowing loudly to the crowd “How can this be? How can this be?” and berated the lad who had committed the offence before everyone present. This was another moment that was frequently recalled thereafter with much hilarity, though at the moment it must have been distressing to the two boys, probably not yet even 15 years of age.

Bonfires

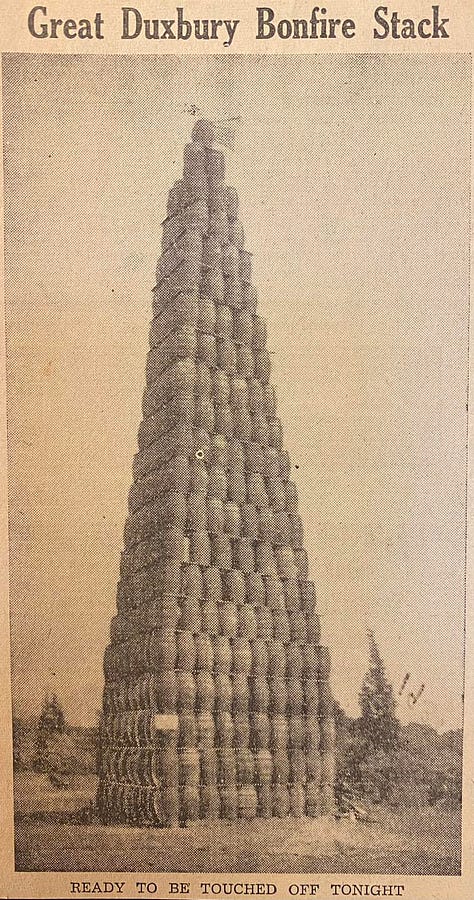

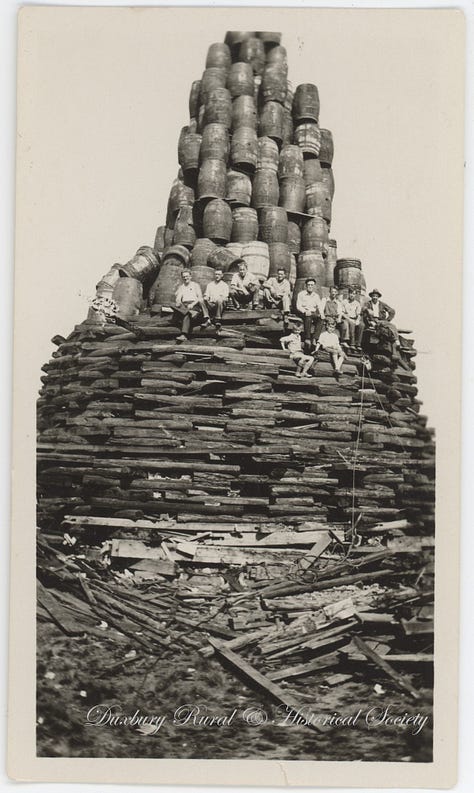

I did not find the bonfire to be very exciting. It consisted in the 1960s of many wooden barrels piled high upon each other, and they would be ignited on July 3rd in the dark of evening. I can testify that there are more interesting things to observe than several hundred barrels consumed in flame.

The memory didn’t provoke much reflection until I moved with family to Ireland, where we worked for years before retiring in France. But in 2010 those memories came back to me, as July 12th approached.

In Northern Ireland July 12th has been traditionally celebrated by Protestants, or more particularly by members of the Orange Order, to mark the Protestant victory in 1690 at the Battle of the Boyne. This battle, between the forces of King William III of Orange (a Protestant) and King James II (a Catholic), assured Protestant domination of the northern counties of Ireland thereafter. It’s believed that bonfires had been used to guide the landing of William of Orange’s ships at Carrickfergus in County Antrim, and were thereafter used terrestrially to guide troop movements. These days massive bonfires are traditionally lit on July 11th in various Unionist areas of the north, and are seen as chauvinistic of Protestant political causes and, frequently, are explicitly hostile to Catholic and Irish Republican interests.

Inevitably I wonder about the connections to the bonfires in my home town. Saint Patrick’s Day in Duxbury, an overwhelmingly Protestant town, was a day when family members wore something green. But at school it was a day where some of my fellow grade-schoolers wore orange, and drew attention to it—knowing that it was anti-Catholic Irish but probably having no idea about its symbolism or origins. I also wondered about the proximity of July 3rd, when Duxbury’s bonfires were usually lit, to July 11th. Was there some connection? If so I expect any explicit relationship was lost long ago, and local lore is more likely to associate such Massachusetts bonfires simply with the founding of the nation—a tradition that continues due solely to historical inertia.

No matter. Ultimately I remember the bonfires as no more interesting than a dumpster fire—which would perhaps be a more fitting symbol these days for July 4th celebrations anyway.

Epilogue

Duxbury is quite a different place these days than when my family lived there. During our last years living there as children a massive project was underway to connect Boston to Cap Cod—the Southeast-Expressway—and it passed barely a mile from where we lived. It became one of the catalysts that has forever changed the town, in every way. There are no more farms in town; I remember reading a newspaper article about “the last farm in Duxbury” years ago. The ubiquitous cranberry bogs are fewer, too, some having been filled to provide land for housing developments. The population has grown significantly, from fewer than 3,000 in the early 1960s to 16,090 in the 2020 U.S. Census. And the town is more diverse in some ways: the Grange Hall is now a synagogue; and Irish and Catholic families are perhaps now in the majority, whereas in my childhood a very tangible prejudice among the old “Yankee” families against both could be easily discerned. When living in Dublin decades later, I was astonished when a professor of history who, upon learning I’d grown up in Duxbury, exclaimed “The Irish Riviera!” I’d never heard this expression. The few acquaintances I maintain from the old days often call it “Deluxebury.”

It seems nevertheless that Duxbury Days continues, at least with a parade and a much reduced bonfire made from wooden palettes, ignited on Duxbury Beach. But if you want to enjoy a carnival midway, there is always the annual Marshfield Fair in the town next door.

If you enjoyed this or my other posts, feel free to …

John, I love the nostalgia and the sense of place you evoke with this piece. It made me reflect on my own Fourth of July childhood memories. I do not have anything so vivid for when I was young, although I know we spent them outside at the beach with family barbequing, and then went downtown in the evening to hear the concert in Chicago's Grant Park and watch the fireworks.

When I was older there were many years of the Taste of Chicago, a festival where restaurants from all over the city offering tastes for a few tickets that we bought at booths in the beginning. It would be hot, sometimes 100 degree, and the police would go through on horses that left big droppings on the sidewalks which one had to watch out for along with being shoved along in huge crowds. People would come from other states to attend. Still, it had a very local feel to it.

In some years there were over 1 million people there and it would take hours to be able to leave after the fireworks at the lake front. I recall one year needing 3 hours to leave and the subways being packed wall to wall, up the stairs and out on the streets. It was craziness. After a man with a knife shoved me and my friends trying to get through, I stopped going.

As a parent we enjoyed participating in our own neighborhood festival with parade in which the children would decorate their bikes, scooters, and parents would decorate their strollers and buggies. It sounds like yours in that is was smaller and local. No carnival but we would march through the neighborhood, where many local politicians came out and joined us. It end at a nearby park where there was a petting zoo, Black cowboys would come and ride children on their horses, and there were many games, and local high school bands would play while their cheerleaders did dances. My favorite was the water melon seed spitting contest for the obvious reason that we got to eat copious amounts of watermelon and spit the seeds. We would bring a blanket and picnic and together with friends and family hang out most of the day. Again we would go to the lakefront in the evening but in our neighborhood where we could see the far off fireworks in the city center light the night sky and then walk home in the dark.

This Fourth of July I am in Germany and will be celebrating together with American friends, sans fireworks. My daughter is going to an American diner in her city with friends that are also part American and eating typically American foods, like bbq ribs. She and I were reflecting on whether we were still able to celebrate American independence. I will be celebrating the independence we have had and hopefully will have again. I wish you a Happy Fourth in France John.

I also loved this post. Our town carnival and parade circa mid 60s had some of the same feel, but I don't think there were any side shows, although I was aware they existed here and there, perhaps more out in the country. I'm guessing your memories are a bit earlier. I'm wondering when and how they went out of style and then totally disappeared.