My first memories of Trouants Island are from my father’s final visit there. The year must have been 1956 or 1957, and I still remember the day quite well.

My father’s family had been visiting Trouants Island in Marshfield Hills, Massachusetts, for several decades before that visit. In a short essay about the island, my grandfather, who grew up in Medford, Massachusetts, wrote of his earliest journeys there while still in school to hunt for game birds. Given his birth year of 1875, that would mean he became acquainted with the island at least by 1893, several years before the devastating “Portland storm” of 1898 that changed the topography of the surrounding area. After friends from Medford purchased the island, the Howard family became part of the Medford crowd that headed south each year to spend cherished summers in the island’s rickety cottages, enjoying the sea, sunshine, and homemade ice cream.

My father, Jim Howard (known in childhood as “Jimma”), recalled those trips by car from Medford to Trouants Island. The roads were poor in places and automobile tires were taxed by the journey, requiring them to carry at least two spares to assure same-day arrival.

My recollection of the day we visited long ago begins with talk of when the tides would allow us to drive both on and off the island. The purpose was to close up the Howard family camp. It had been used by the Howards since they purchased it—the cottage that is—from a friend of my grandfather from Jamaica Plain. They therefore owned the cottage, but the ground it stood on was leased. I don’t recall the details of why it had become necessary to give up the camp and cottage, indeed as a child I might never have been told. No matter, the task of closing up the place had fallen to my father and his nostalgia for it was very apparent.

Inside the cottage things seemed primitive compared to home. My father spoke of how the camp stayed cool all summer long because of the sea breezes. “We slept under blankets every night,” he said, and he repeated this often in the years to follow. Especially when nights were hot, or when we were fishing off of Saquish Head in Plymouth and observed the cottages along the beach. He pointed out the kerosene stove, speaking with reverence about the remarkable things my Acadian grandmother, Helen Howard, was able to cook with it. Delicious peanut brittle was cited as proof of her culinary wizardry.

Each of us three children was given the opportunity to choose something in the cottage to take home with us. My brother, Jim Jr., chose a painting of three sailboats that now hangs on a wall at his home in Maine. I chose a pair of brass candlesticks, and I have them still. They are a beautiful art nouveau design and are layered thick with a green tarnish from decades of exposure to salted air. I enjoy telling people the story of how they came to sit on our table at home in France. It’s my one material memory of The Island, as it was always called.

We were given a tour of The Island, too. We stood at its perimeter and my father pointed to a boulder well down the beach. “That’s Grandfather Rock,” he said. “When we were kids that rock was up here on the land.” We also visited the water tower—a small elevated wooden water tank where well water was pumped to provide some water pressure and running water, at least to some of the cottages.

He spoke about summers as a teenager when he would work on Rob Tilden’s farm, picking strawberries and doing farm chores. He developed an extraordinary knowledge of farm implements from this experience. Yankee Magazine used to have a “What Is It” column that often showed a photo of some odd tool. I’m sure my father could have identified all of them, if they came from a farm.

Somewhere during our walk around The Island he spoke of “Blackie,” his pet crow, telling of how the children liked to throw morsels of food into the air and watch Blackie catch them on the fly. One day, a boy tossed up a piece of a shingle which Blackie took, choked on and perished. We heard this story many times in the years after—he loved that bird. Dad had a similar nostalgia for a pet parrot that kept him company while serving on a U.S. Navy crash boat in the Pacific theatre of World War II. At the war’s end he wasn’t allowed to take the little parrot home with him. He spoke of this often, too; I wonder now if the loss reminded him of losing his beloved pet crow on The Island.

There were other stories, too. Of rowing to Humarock to buy a soft drink. My father and other boys set off rowing across the water. My father said he was holding his nickel for the soft drink so hard that the image of the buffalo was impressed into his hand. When they got to the store, though, something took hold of him and he bought a drink called “Old Stout.” It was a near beer, and his disappointment was sufficiently profound that he repeated the story for the next seventy years.

It seems he rowed everywhere on those warm summer days. He had a remarkable skill at sculling—a style of propelling a small boat, in his case a pram—by moving the oar off the stern in thwartwise fashion (that is, a figure-eight motion). The way he did it you’d think the boat had a propellor. He claimed that during the summer a certain muscle on his right arm would develop and become prominent from this activity. I tried it many times but never mastered the technique, nor did that muscle grow. For him, it was second nature.

In the years after the camp on The Island was closed we would sometimes visit with friends my father knew from there. The Emerys in Marshfield Hills were another Medford family, and on the way to visiting them we would pass Macomber’s Way off Summer Street. My father would say, “That’s the way to The Island.” Sometimes we’d take a detour and just drive down the road to look at it across the shallow water, then turn back and continue on. We also visited with the Alexandersons, also summer residents of The Island, who had a wonderful home overlooking the sea in Brant Rock, a site and a structure no doubt influenced by the experience of summers on Trouants Island. It seems The Island left its imprint on everyone who had spent splendid summers there.

My grandfather, known as Jack, was a true outdoorsman. He loved the outdoors, animals, nature in general, and spent as much time as a family man could in the woods of Maine and New Brunswick, but summers were on Trouants Island. As a sportsman he came to believe that there was more sport in hunting with a camera than a rifle, and he became an accomplished amateur photographer. Most of the hundreds of photos in his legacy were captured in the northern woods, but there are several hundred of family, too, and most were taken on Trouants Island.

The photographs tell their own story, though it is sometimes challenging to infer details such as date, place and who all those people are. But in that way they are like other memories, where names and places can fade away, while the outline of the story remains the same.

The photographs have lain dormant for decades in wooden boxes and carefully wrapped packages of glass plates and celluloid film. They came to me after first passing to my father and for years they were on my list of good intentions. Now that I am finally processing them—cleaning, identifying, reproducing, developing, and documenting— stories unknown to me and my siblings have emerged, not to be heard but to be seen.

I heard so much about my father’s brothers growing up. Especially about my Uncle Brooks (born 1908), a smart young man who died too young, falling from a tree on the campus of Massachusetts Agricultural College (now the University of Massachusetts). Like his father he had a love of nature and was studying zoology, dreaming of becoming an ornithologist like his hero Edward Howe Forbush. He was known by other students for the large number of specimens he collected and kept in his room. One day in April 1929, investigating a crow’s nest high in a tree, he fell and lost his life. His death was mourned by my grandparents ever thereafter. My grandmother would sit and knit—her hands were never idle—and would call out “poor Brooks” from time to time as she continued her work.

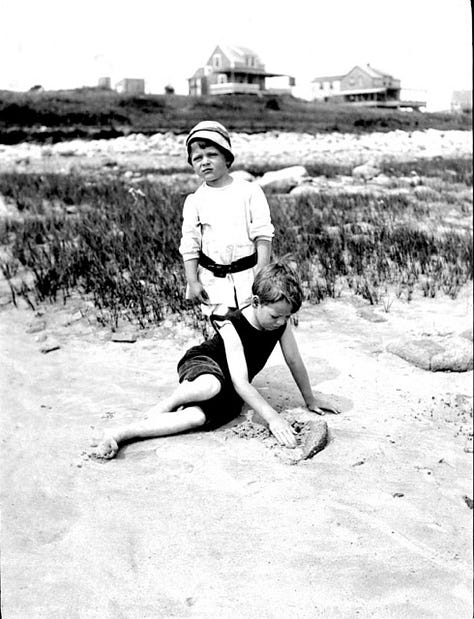

Yet in the photos from The Island, there he was, alive and happy, just a small boy. Almost always with his brother Frank, who was known as “Brud,” he seemed both playmate and protector. The two were seen together, little boys, with clam forks digging in the sand, drawing water playfully from a pump, or standing with bare feet on the sand or in the water of The Island’s shore.

Other photos with the boys’ mother or father give a glimpse of island life, too. The boys watching Jack clean fish atop a wooden barrel, or with their mother, Helen, as she joined them in the water or watched over them and their friends.

There were many children on The Island in those days. I can spot and name the Emery children. My father as an adult worked with one of the Emery twins; those island connections seemed to last. The others are nameless to me, but have become familiar faces as I’ve worked carefully through all the photographs. My grandfather wrote in his essay on The Island that it was a great place for kids, but the strong tides of the estuary demanded vigilance of the adults, and there are many images of the grown-ups as well. Boating, fishing, eating ice cream near the beach.

The photographs give up quiet secrets as well. Among them are a few from the family home in back in Medford—a tiny infant girl in an old-fashioned stroller. My siblings and I remembered stories of children who did not survive; my sister’s memories are clearest, she heard it directly from our grandmother. Indeed with some research we learned that Helen Avery Howard was born on 13 March 1916. She was named after her mother, Helen, and her Acadian maternal grandmother, whose family name at birth was Avery. The pattern of the forenames fit that of the first born boy, named for his father but also his grandmother, who was born into the Brooks family of Meriden, Connecticut. Tit for tat, as my sister says?

This lovely child, the aunt we never knew, died that year on October 12, seven months or 213 days after birth. The death certificate records that she fell victim to an intestinal condition that likely could have been corrected had she been born a century later. The photographs from the summer of 1917 betray the mourning that must have followed the family to The Island that year. Helen appears in none of them. And the boys—so odd to see their faces not smiling but often with eyes cast downward. Was it me conjuring this memory, projecting my sense of the grief from a child’s death onto the faces of those playful boys? I think not, the photographs speak too clearly.

By the summer of 1918 there was consolation and joy once again. My father, Jimma, was born a year and a day after Helen Avery had slipped away, bringing comfort and new life to the family and The Island. There he is, remembered as a happy, smiling and healthy baby in the photographs. Sitting in a wooden box on the unpainted cottage porch, waving his hands, maybe responding to his mother’s patty-cake as Jack snapped the camera shutter. Or with his brothers, sitting together in the grass, the Howard camp in the distance. I’d know that smile on Jimma’s face anywhere, and apparently at any age.

There is a gap in the memories, maybe there was also a period when it was not so easy to travel to The Island for the summer. The last photos from The Island come from 1928. My father was by then a boy with a pet crow. Brooks was a young man, home from college for the summer and no doubt carefully watching the birds and recording observations in his diaries. Jack and Helen are older, and the rickety cottage is still there, harbouring its caretakers under blankets on breezy summer nights.

Brooks died the next April. My grandfather wrote about his death in several places. He never said “passed away” or used some other euphemist phrase. He always wrote “killed.” Is that why the photographs, the visual memories of splendid summers on The Island, ceased in 1928? When Brooks climbed that tall tree in Amherst, Massachusetts, might he have been thinking of his little brother Jimma and the loss of his beloved pet crow? Still, island summers continued in the years that followed. The camp was last used in the late 1940s and early 1950s by my uncle Frank (“Brud”) and his wife, Gladys. Then we made that trip to close it down.

Trouants Island is different now. No doubt it is smaller from erosion, as the “old timers” once predicted—Grandfather Rock must be well off shore. The cottages with their kerosene stoves and lamps, metal bath- and wash-tubs on the porches, and their outdoor wooden privies are long gone. The houses are now large and luxurious, served by up-to-date utilities and code-compliant roads, suitable for year-round residency.

But happy memories of The Island as it was are still there, lent to a few in stories recalled, and photographs that lend us their memories too.